(4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926)

O trees of life, oh, what when winter comes?

We are not of one mind. Are not like birds

in unison migrating. And overtaken,

overdue, we thrust ourselves into the wind

and fall to earth into indifferent ponds.

Blossoming and withering we comprehend as one.

And somewhere lions roam, quite unaware,

in their magnificence, of any weaknesss.

But we, while wholly concentrating on one thing,

already feel the pressure of another.

Hatred is our first response. And lovers,

are they not forever invading one another's

boundaries? -although they promised space,

hunting and homeland. Then, for a sketch

drawn at a moment's impulse, a ground of contrast

is prepared, painfully, so that we may see.

For they are most exact with us. We do not know

the contours of our feelings. We only know

what shapes them from the outside.

Who has not sat, afraid, before his own heart's

curtain? It lifted and displayed the scenery

of departure. Easy to understand. The well-known

garden swaying just a little. Then came the dancer.

Not he! Enough! However lightly he pretends to move:

he is just disguised, costumed, an ordinary man

who enters through the kitchen when coming home.

I will not have these half-filled human masks;

better the puppet. It at least is full.

I will endure this well-stuffed doll, the wire,

the face that is nothing but appearance. Here out front

I wait. Even if the lights go down and I am told:

"There's nothing more to come," -even if

the grayish drafts of emptiness come drifting down

from the deserted stage -even if not one

of my now silent forebears sist beside me

any longer, not a woman, not even a boy-

he with the brown and squinting eyes-:

I'll still remain. For one can always watch.

Am I not right? You, to whom life would taste

so bitter, Father, after you - for my sake -

slipped of mine, that first muddy infusion

of my necessity. You kept on tasting, Father,

as I kept on growing, troubled by the aftertaste

of my so strange a future as you kept searching

my unfocused gaze -you who, so often since

you died, have been afraid for my well-being,

within my deepest hope, relinquishing that calmness,

the realms of equanimity such as the dead possess

for my so small fate -Am I not right?

And you, my parents, am I not right? You who loved me

for that small beginning of my love for you

from which I always shyly turned away, because

the distance in your features grew, changed,

even while I loved it, into cosmic space

where you no longer were...: and when I feel

inclined to wait before the puppet stage, no,

rather to stare at is so intensely that in the end

to counter-balance my searching gaze, an angel

has to come as an actor, and begin manipulating

the lifeless bodies of the puppets to perform.

Angel and puppet! Now at last there is a play!

Then what we seperate can come together by our

very presence. And only then the entire cycle

of our own life-seasons is revealed and set in motion.

Above, beyond us, the angel plays. Look:

must not the dying notice how unreal, how full

of pretense is all that we accomplish here, where

nothing is to be itself. O hours of childhood,

when behind each shape more that the past lay hidden,

when that which lay before us was not the future.

We grew, of course, and sometimes were impatient

in growing up, half for the sake of pleasing those

with nothing left but their own grown-upness.

Yet, when alone, we entertained ourselves

with what alone endures, we would stand there

in the infinite space that spans the world and toys,

upon a place, which from the first beginnniing

had been prepared to serve a pure event.

Who shows a child just as it stands? Who places him

within his constellation, with the measuring-rod

of distance in his hand. Who makes his death

from gray bread that grows hard, -or leaves

it there inside his rounded mouth, jagged as the core

of a sweet apple?.......The minds of murderers

are easily comprehended. But this: to contain death,

the whole of death, even before life has begun,

to hold it all so gently within oneself,

and not be angry: that is indescribable.

Translated by Albert Ernest Flemming

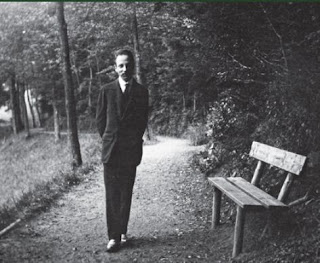

Rilke három évesen

Duinói Elégiák - A NEGYEDIK ELÉGIA

Duineser Elegien - Die Vierte Elegie

Ó, élet fái, mikor ér a tél?

Nem értünk egyet. Ösztön, mint a vándor-

madarat, nem visz. Késve-maradozva

kapunk föl egy-egy szélre hirtelen

s hullunk megint le részvétlen tavakra.

Nyílást, hervadást egyformán tudunk.

Bár oroszlánok járnak valahol még,

s míg pompáznak, nem ismernek hanyatlást.

S mi, egyet vélve váltig, már a másik

gerjedését érezzük. A közellét:

ellenségünk. Nem párkányon bolyongnak

egymásban is a szeretők, noha

egymásnak hont, hajszát, távolt igértek?

Az ellentét alapja készül itt

a perc rajzához, fáradságosan,

hogy lássuk; mert nagyon világosak

velünk. Nem ismerjük az érzés

kontúrját, csak mi kintről alakítja.

Ki nem ült szíve függönye előtt

szorongva? Szétnyílt: búcsújelenet volt,

könnyen megérthető. Az ismerős kert,

s halkan megbillent -: csak most jött a táncos.

Nem az. Elég. S bármilyen könnyed is,

álruhában van, polgár lesz belőle

és konyháján át megy be a lakásba.

Nem kellenek e féligteli maszkok,

inkább a bábu. Az telt. El fogom

tűrni az irhát és a drótot és

bamba arcát. Itt. Előtte vagyok.

Ha kihunynak is a lámpák, ha azt

mondják is: Vége - s szürke léghuzattal

meg is csap a színpadról az üresség,

s ha nem is ül már néma őseim

közül velem itt senki, nő se, sőt a

kancsal barnaszemű fiú se: mégis

maradok. Mindig van látnivaló.

Nincs igazam? Kinek oly keserű volt

a lét, létemet ízlelve, apám,

ki kényszerem első zavart levét,

ahogy nőttem, ízlelted újton-újra,

s jövőm idegen zamatán tünődve

vizsgáltad, ha ernyedten föltekintek -

apám, ki bennem, mióta halott vagy,

reményem mélyén gyakran ott szorongsz

s közönyt, a holtak közönyét, közöny-

országokat adsz föl kis sorsomért:

nincs igazam? S nincs igazam, ti, kik

szerettetek, felétek sarjadó

szeretetemért, melytől untalan

eltértem, mert a tér orcátokon,

mivel szerettem, világtérbe tágult,

s abban nem voltatok már... Ámha kedvem

van a bábszínpad előtt várni! nem:

oly merőn nézni, hogy fölérni végül

nézésemmel, játékosul csak angyal

rángathatja a bábukat magasba.

Angyal és bábu: az lesz csak a játék.

Így olvad össze, amit szűntelen

megosztunk, amíg itt vagyunk. Csak így

alakul ki az egész pálya íve

évszakainkból. Ilyenkor fölöttünk

az angyal játszik. Ők ne sejtenék, lásd,

a haldoklók, hogy mennyire csupán

ürügy itt minden művünk? Semmi nem

egy önmagával. Ó, gyerekkori

órák, mikor az ablakok mögött

több volt múltnál, s nem volt jövő előttünk!

Nőttünk, igaz, s mohón is, hogy hamar

nagyok legyünk, félig értük: akiknek

egyebük sem volt már, mint hogy nagyok.

S mégis boldoggá tett a Maradandó,

utunk egyedülségében - s csak álltunk

a senkiföldjén, játék és világ közt,

a térben, mely a kezdet kezdetétől

egy tiszta tény számára született.

Ki mutat gyermeket, úgy, amilyen? ki

emeli égre? ki adja kezébe

a messzeség mércéjét? szikkadó

szürke kenyérből ki készíti - vagy, szép

alma csutkáját, szájában ki hagyja

a gyermekhalált?... Gyilkosba belátni

könnyű. De ez: a halált, az egészet,

s még az élet előtt, ilyen szelíden

tartalmazni, s gonosznak mégse lenni:

leírhatatlan.

Rónay György fordítása

______

Rainer Maria Rilke versei, Európa Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 1983