.

HETEDIK ECLOGA

Látod-e, esteledik s a szögesdróttal beszegett, vad

tölgykerités, barakk oly lebegő, felszívja az este.

Rabságunk keretét elereszti a lassu tekintet

és csak az ész, csak az ész, az tudja, a drót feszülését.

Látod-e drága, a képzelet itt, az is így szabadul csak,

megtöretett testünket az álom, a szép szabadító

oldja fel és a fogolytábor hazaindul ilyenkor.

Rongyosan és kopaszon, horkolva repülnek a foglyok,

Szerbia vak tetejéről búvó otthoni tájra.

Búvó otthoni táj! Ó, megvan-e még az az otthon?

Bomba sem érte talán? s van, mint amikor bevonultunk?

És aki jobbra nyöszörg, aki balra hever, hazatér-e?

Mondd, van-e ott haza még, ahol értik e hexametert is?

Ékezetek nélkül, csak sort sor alá tapogatva,

úgy irom itt a homályban a verset, mint ahogy élek,

vaksin, hernyóként araszolgatván a papíron;

zseblámpát, könyvet, mindent elvettek a Lager

őrei s posta se jön, köd száll le csupán barakunkra.

Rémhirek és férgek közt él itt francia, lengyel,

hangos olasz, szakadár szerb, méla zsidó a hegyekben,

szétdarabolt lázas test s mégis egy életet él itt, -

jóhírt vár, szép asszonyi szót, szabad emberi sorsot,

s várja a véget, a sűrü homályba bukót, a csodákat.

Fekszem a deszkán, férgek közt fogoly állat, a bolhák

ostroma meg-megujúl, de a légysereg elnyugodott már.

Este van, egy nappal rövidebb, lásd, ujra a fogság

és egy nappal az élet is. Alszik a tábor. A tájra

rásüt a hold s fényében a drótok ujra feszülnek,

s látni az ablakon át, hogy a fegyveres őrszemek árnya

lépdel a falra vetődve az éjszaka hangjai közben.

Alszik a tábor, látod-e drága, suhognak az álmok,

horkan a felriadó, megfordul a szűk helyen és már

ujra elalszik s fénylik az arca. Csak én ülök ébren,

féligszítt cigarettát érzek a számban a csókod

íze helyett és nem jön az álom, az enyhetadó, mert

nem tudok én meghalni se, élni se nélküled immár.

Lager Heidenau, Žagubica fölött a hegyekben, 1944. július

The Seventh Eclogue

Do you see the night, the wild oakwood fence lined with barbed wire,

and the barracks, so flimsy that the night swallowed them?

Slowly the eye passes the limits of captivity

and only the mind, the mind knows how tight the wire is.

You see, dear, this is how we set our imaginations free.

Dream, the beautiful savior, dissolves our broken bodies

and the prison camp leaves for home.

Ragged, bald, snoring, the prisoners fly

from the black heights of Serbia to the hidden lands of home.

Hidden lands of home! Are there still homes there?

Maybe the bombs didn't hit, and they

are, just like when we were "drafted"?

Next to me, on my right, a man whines, another one lies on my left. Will they go home?

Tell me, is there still a home where they understand all this?

Without commas, one line touching the other,

I write poems the way I live, in darkness,

blind, crossing the paper like a worm.

Flashlights, books – the guards took everything.

There's no mail, only fog drifts over the barracks.

Frenchmen, Poles, loud Italians, heretic Serbs, and dreamy

Jews live here in the mountains, among frightening rumors.

One feverish body cut into many pieces but still living the same life,

it waits for good news, the sweet voices of women, a free, a human fate.

It waits for the end, the fall into thick darkness, miracles.

I lie on the plank, like a trapped animal, among worms. The fleas

attack again and again, but the flies have quieted down.

Look. It’s evening, captivity is one day shorter.

And so is life. The camp sleeps. The moon shines

over the land and in its light the wires are tighter.

Through the window you can see the shadows of the armed guards

thrown on the wall, walking among the noises of the night.

The camp sleeps. Do you see it? Dreams fly.

Frightened, someone wakes up. He grunts, then turns in the tight space

and sleeps again. His face shines. I sit up awake.

The taste of a half-smoked cigarette in my mouth instead of the taste

of your kisses and the calmness of dreams doesn’t come.

I can’t die, I can’t live without you now.

Lager Haidenau, in the mountains above Žagubica July 1944

-Translated from the Hungarian by Steven Polgar, Stephen Berg, and S. J. Marks

The Seventh Eclogue

Dusk; and the barracks, the oak stockade with its hem

of cruel wire, they are floating – see! they melt in the night.

The faltering gaze unlocks our frame of captivity

and only the brain can measure the twist of the wire.

But see too, my love, only thus may the fantasy free itself:

dream the redeemer dissolves the wreck of the body,

and off they go homeward, the whole campful of prisoners.

Snoring they fly, the poor captives, ragged and bald,

from the blind crest of Serbia to the hidden heartland of home!

The hidden heartland.– O home, O can it still be?

with the bombing? and is it as then when they marched us away?

and shall those who moan on my left and my right return?

Say, is there a country where someone still knows the hexameter?

As thus in darkness I feel my way over the poem,

shorn of its crown of accents, even so do I live,

blind, like an inchworm, spanning my hand on the paper;

flashlight, book, the lager guards took away everything,

and the mail doesn’t come, and fog descends on the barracks.

Amid rumors and pests live the Frenchman, the Pole, loud Italian,

the Serbian outcast, the musing Jew in the mountains:

one life in all of these tattered and feverish bodies,

waiting for news, for a lovely womanly word,

for freedom – for an end how dark soever – for a miracle.

On boards among vermin I lie, a beast in a cage;

while the flies’ armies rest, the fleas renew the assault.

It’s night. Confinement’s another day shorter, my love;

life, also, is less by a day. The camp is asleep.

The moonlight rekindles the landscape, retightens the wire;

you can watch through the window the shadows of guards with guns,

pacing, cast on the wall in the many voices of night.

The camp is asleep. See their dreams rustle, my love;

he who startled up snores, turns in his narrow confinement,

falls asleep again, face in a shine. Alone, awake,

I sit with the taste of a cigarette-end in my mouth

instead of your kiss, and the melting dream doesn’t come, for

I neither can die nor live any more without you.

Lager Heidenau: in the mountains above Zagubica. July 1944.

-Translated by Ben Turner and Zsuzsanna Ozsváth

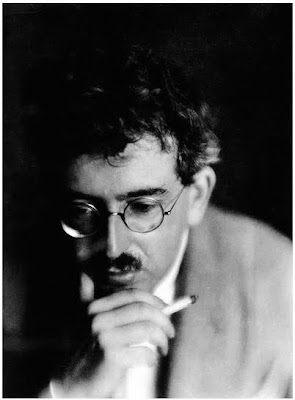

Radnóti Miklós és felesége Fanni (Budapest, 1941)

Miklós Radnóti with his wife Fanni (Budapest, 1941)

[Forrás / Source: Radnóti Miklós, Fényképek, Osiris, 1999]

THE SEVENTH ECLOGUE

Evening approaches the barracks, and the ferocious oak fence

braided with barbed wire, look, dissolves in the twilight.

Slowly the eye thus abandons the bounds of our captivity

and only the mind, the mind is aware of the wire’s tension.

Even fantasy finds no other path towards freedom.

Look, my beloved, dream, that lovely liberator,

releases our aching bodies. The captives set out for home.

Clad in rags and snoring, with shaven heads, the prisoners

fly from Serbia’s blinded peaks to their fugitive homelands.

Fugitive homeland! Oh -- is there still such a place?

still unharmed by bombs? as on the day we enlisted?

And will the groaning men to my right and my left return safely?

And is there a home where hexameters are appreciated?

Dimly groping line after line without punctuation,

here I write this poem as I live in the twilight,

inching, like blear-eyed caterpillar, my way on the paper;

everything, torches and books, all has been seized by the Lager

guard, our mail has stopped and the barracks are muffled by fog.

Riddled with insects and rumours, Frenchmen, Poles, loud Italians,

separatist Serbs and dreamy Jews live here in the mountains –

fevered, a dismembered body, we lead a single existence,

waiting for news, a sweet word from a woman, and decency, freedom,

guessing the end still obscured by the darkness, dreaming of miracles.

Lying on boards, I am a captive beast among vermin,

the fleas renew their siege but the flies have at last retired.

Evening has come; my captivity, behold, is curtailed

by a day and so is my life. The camp is asleep. The moonshine

lights up the land and highlights the taut barbed wire fence,

it draws the shadow of armed prison guards, seen through the window,

walking, projected on walls, as they spy the night’s early noises.

Swish go the dreams, behold my beloved, the camp is asleep,

the odd man who wakes with a snort turns about in his little space

and resumes his sleep at once, with a glowing face. Alone

I sit up awake with the lingering taste of a cigarette butt

in my mouth instead of your kiss, and I get no merciful sleep,

for neither can I live nor die without you, my love, any longer.

-Translated by Thomas Ország-Land, 2009.

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................